URBAN AND POOR

An Everyday Guide to Development Pt 3

Cities are great. Economist Edward Glaeser calls them “our species greatest invention”. Cities have been correlated with human prosperity for thousands of years - and there are no significant indications that things will not continue that way. There are many reasons why cities are important for humans. First is safety. For the early part of our history we live in nomadic small bands and tribes. Living in small scattered groups increases the risk of harm - from predatory animals to more organized bandit tribes. The discovery of agriculture made life more sedentary and allowed population, and thus density to grow. Francis Fukuyama argued that population density was instrumental in the development of states and institutions. If a settlement is dense, it makes coordination and cooperation easier - and people can better organize to defend themselves against external threats. Dense populations and settlements allowed the evolution and experimentation of different cooperative arrangement that facilitated coexistence, sharing arrangements, dispute resolution and other forms of social mechanisms and norms.

CITIES AND PROSPERITY

Cities are defined by two distinct features. One is a high level of population density - a geographic area with one million people or more. The second feature involves the institutional arrangement or governance mechanism that prevents the collapse or dissolution of such a settlement. But both features by themselves do not make for a thriving population. Density may increase survival rate and further cooperation, but it does not automatically lead to a higher economic output. Dense settlements exhibit “loose Malthusian constraints” and are highly productive. We can say the same of modern cities. They always attract productive people, and they are richer than rural settlements. Investor Paul Graham writes that cities makes people ambitious.

Great cities attract ambitious people. You can sense it when you walk around one. In a hundred subtle ways, the city sends you a message: you could do more; you should try harder.

The surprising thing is how different these messages can be. New York tells you, above all: you should make more money. There are other messages too, of course. You should be hipper. You should be better looking. But the clearest message is that you should be richer.

What I like about Boston (or rather Cambridge) is that the message there is: you should be smarter. You really should get around to reading all those books you've been meaning to.

When you ask what message a city sends, you sometimes get surprising answers. As much as they respect brains in Silicon Valley, the message the Valley sends is: you should be more powerful.

That's not quite the same message New York sends. Power matters in New York too of course, but New York is pretty impressed by a billion dollars even if you merely inherited it. In Silicon Valley no one would care except a few real estate agents. What matters in Silicon Valley is how much effect you have on the world. The reason people there care about Larry and Sergey is not their wealth but the fact that they control Google, which affects practically everyone.

I was born in Lagos, but work had my parents relocate to a different part of the country. So I grew up in a quiet, relatively sparse, clean and serene neighbourhood. Every time we visited Lagos for holidays, I was always angry and sometimes reduced to tears. It was rough, dirty, violent and just too unpleasant for my psyche. I could not understand my mother’s fascination with this place. Even with stories she tells about fun times she had in her youth, I still hated the place. But my mother desperately wanted to be back. “Lagos is where it is happening”, she always said.

When I was 13, we moved back to Lagos. It felt like my worst nightmare. Everything I hated about this city now became my daily life. But something else happened. Other than my mother’s inexplicable happiness, our household also became richer. We bought our first car, and moved from a rented flat a few years after. I also grew to appreciate the advantages of living in a city. Having the first picks of culture, knowledge and social happenings were very fruitful for my growing mind. And as I grew up to live and work in the same city, I always perform a crude survey on friends and colleagues who just moved into Lagos. They hate the demonic traffic congestion, the soaring cost of housing, the toxic quality of the air, and the loud roguish social culture. But none of them want to move elsewhere. They all want to make a better life for themselves in Lagos. The correlation between urbanization and income regardless of any contextual dynamic, has remained very strong and robust. The GDP of Lagos is estimated to be between 15-20% of Nigeria’s despite being only 0.1% of its land mass.

Life has changed from my childhood, but most of you can tell similar stories about other cities in Nigeria like Benin, Portharcourt, Aba, Onitsha, Ibadan, Jos and Kano. Political scientist Alice Evans concluded from her study in Cambodia that cities erode gender inequalities. By raising the opportunity costs of not working, women in cities are incentivized to work and earn more. Also their exposure to modern work environment means they are treated with greater equality than rural women. Where does the inherent advantages of cities reside? The most common explanation is Agglomeration effect. Cities bring people closer together and thus reduce the cost of business. The large population of cities also mean business can be done at scale. Several models and studies of trade have found that producers cluster around cities to be able readily access the largest markets for their goods. The “thickness” of economic activities give cities their enrichment effect.

URBANIZATION WITHOUT GROWTH

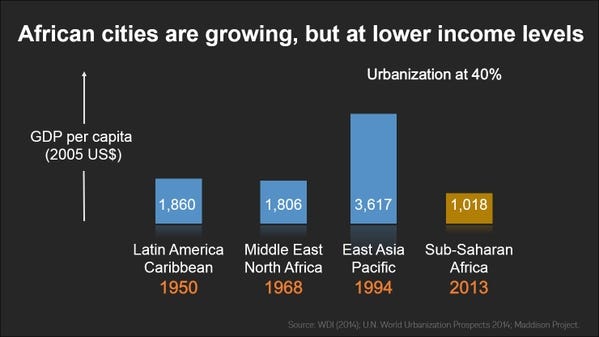

If cities have huge economic and social benefits, then you will expect urban areas to have a “pull” effect on people. The potential gains from moving to a city will always encourage more people to move. Note that the reverse may also be true - that is economic life in rural settlements may become sufficiently unproductive, hence “pushing” people into cities. This is why urbanization is happening at a quickening pace all over the world. Africa is urbanizing even faster than historical trends, and urbanization in Nigeria is equally rapid - and not about to slow down. What is curious however is that african cities have significantly lower income than past trends in other parts of the world. This means that residents of African cities like Lagos are on average poorer without rising living standards.

There are clear governance failures in most of these cities. Majority of residents in Lagos live in slums without waste management, sewage system and drainage channels. In 1990, according to the UN, around 90% of the population of Lagos have access to clean water, today its less than 60% and falling. Over 70% of waking hours are spent in traffic congestion. And uncontrolled sprawl makes getting around the city a hellish experience. The problem with cities like Lagos cannot be divorced from the problems that afflict the macroeconomic environment in which they reside. Unlike the 400 or so years that preceded it, rapid urbanization in the developing world has not delivered commensurate economic growth and prosperity. This has led to the proliferation of poor mega-cities and increased acreage of city-slums. Even more worrying is the pattern of within-city inequality and unequal mobility that has come to plague most cities in the developing world.

STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION

The profile of dominant economic activities in cities have also changed over the years. Suppose it takes 100 farmers to grow 100 tonnes of rice in a farm in Benue. Now if the farm employs the use of technology that cuts the manpower down to 50 people. Not so long ago, those extra 50 farmers will move to cities to work in factories making industrial goods that the 50 richer farmers will demand - maybe home appliances, house furniture or whatever. Even more demand from existing city workers - plant managers, line supervisors, - will require even more people to move from farming to industry. This will further pull people away from farming. Economic activities in cities have shifted from manufacturing into services. Industries like finance, insurance, legal service, health service, transportation have come to dominate. These are essential services, but the increase in their demand has shifted the economic pattern in cities from production to consumption. This is a subtle and complicated point. For example, the demand for orange peelers can be growing faster than the demand for oranges in Lagos. This moves workers from growing oranges to peeling along that value chain. Since the launch of Uber in Johanesbourg in 2013, there have been over 70 new ride-hailing apps launched in Africa. More apps mean more people move into transportation services. The growth of these services is not bad. The wrinkle is that such services do not add to the stock of capital goods in an economy - and may have a slower and narrower enrichment effect in African cities. Adair Turner believes the growth of services might make productivity irrelevant in the future. This is because they can be “zero-sum” - where everybody is competing for a piece of a fixed cake. So we might be looking at a future economy where there are more “Agritechs” firms than actual agricultural productivity. If this trend does indeed continue, income growth and urbanization in cities like Lagos may be permanently decoupled.

CITIES AND LEARNING

Lowering the cost of contact and connection between people is not the magic wand for enrichment in cities. If the prospect of prosperity is the “pull” effect of cities, then it means such prospects are realized by people learning new skills. And lowering the distance between people lowers the cost of learning. The learning effect of cities also holds for firms. Companies clustered around cities can not only access skilled workers easily, they can also quickly catch-up with an innovative competitor through learning. The economic benefits of moving to a city are often estimated through the stated agglomeration effects and human capital externalities. But learning models provides the right foundation for such explanations to have any predictive value. Empirical studies have shown that people do not experience instant income improvements when they move to cities. Rather it takes a while to learn a new skill and then benefit from its mastery and expertise.

I believe learning can tell us two things about the slow growth of income in African cities. Structural transformation may have created significant learning barriers for people now moving into cities. It may have been relatively easy for people to learn to be factory workers 30 years ago than learning to be bank tellers and marketing associates today. Secondly, learning opportunities may be restricted by the overall poor quality of human capital in many African nations. If education levels deteriorate and teach very little practical skills, then human capital can become lower over time. This creates barriers to learning, and people will increasingly choose jobs with less steep learning curves and low productivity.

CHARTER CITIES

For cities to thrive and become a true economic engine of prosperity; they need to facilitate connection and learning. Paul Romer believes what makes this possible in cities are rules. Simple rules like which side of the road to drive and traffic lights help organize mobility in cities. Other rules like clear distinction between public and private spaces can organize human interaction and economic activities in a metropolis. But governments often lack the capability or the incentive to enforce good rules in most developing countries. And since there is strong inertia against sweeping reforms, these cities become stuck in a dysfunctional equilibrium. This led Romer to propose “charter cities” as a way around this problem. Rules are not just about restrictions. There are “market rules” - which let businesses operate freely provided they do not have uncompensated negative externalities. There are also safety rules that protects city-dwellers from air pollution.

It can be challenging to change the incentives in existing cities, and fashion better rules that unlocks prosperity. But charter cities provides a fresh start. Paul Romer’s original framing involves three elements - 1. Uninhabited land. 2. Charter. 3. Choices. Many critics have balked at this idea. The idea of foreign charters is a violation of national sovereignty for some. While some also worry that the new cities will just be “walled gardens” for the rich and will not represent a full range of choices. I think the critiques fail in many ways. We already do many of these things. Private projects like Redemption City(by the RCCG) and Eko Atlantic City are charter cities in everything but name. While you can see public urination in Ketu or open defecation in Makoko, you cannot even imagine such sights in many of Lekki’s posh estates. The rules are simply not the same. What’s different from a charter city perspective is that these private efforts are not happening at a scale that affects the lives of the majority. The worries about affordability also neglects the fact that scale, particularly in the supply of housing will bring down prices. Most of our existing cities are congested and the supply of housing does not even rise to the scale of the demand, yet people move in to live, work and seek better opportunities. So why can’t providing new living experiences for people be a national policy?

Government can commission new arid lands and plan the public spaces. Let private developers build roads and hundreds of thousands of new homes. Let firms move in to build new factories and offices. Let people freely move in and rent or buy houses. Everything dysfunctional about current cities can be reorganized in these new zones. There will be a digital a record of every household so taxation can be effective. You can start with congestion pricing for car traffic without motivated political opposition. You can plan transport networks around buses and mass transit to control air pollution. You can have a clean air law . You can have a city police that is well compensated, effective , does not take bribes or randomly “discharge” bullets. The economic benefits of city zones like this can be massive. Functioning cities with goods rules are catalysts for growth. Shenzhen, Deng Xiaoping reform experiment with a fishing village that became one of the most prosperous cities on earth is a good example. At the height of China’s fast growth era of 10% national income growth, Shenzhen was averaging 23%. Think about that.

The reason we think ideas like charter cities cannot work is because of a central bias about public policy. We usually think unconstrained choices and ambition are only important in the context of private actions. We think public policy should be guided primarily by promises of egalitarianism and equality of outcomes. We think large-scale social engineering should not mimick markets and try to help people realize choice they would make on their own. This is why we can't have nice things. We need to think differently. Markets, choices, options are social concepts and tools. We should embrace new thoughts, experimentation and adaptations that can co-opt them for long run prosperity.